People Pleasing

Where Does People Pleasing Come From?

People pleasing is a coping mechanism we learned at some point to navigate our environment and get our needs met. To better understand the behavior, it’s useful to understand how attachment works. According to Dr. Becky Kennedy, love is a basic need, as important as water, food, and shelter. When it goes unmet, it creates a “primal panic akin to starving.” As she explains, “attachment is an evolutionary system that motivates children to seek proximity to caregivers and establish connection. We can’t really get our needs for love and connection met on our own until we are adults. This time of social and emotional development overlaps with how our brains are wiring around what to expect in the world and what is safe.”

A secure attachment develops when the child can freely explore the world because the child has a “secure base” (or reliable caregiver) to return to. A securely attached child learns to expect comfort when distressed and therefore develops the trust to take risks. On the other hand, an anxiously attached child did not have a secure base and thus did not develop a sense of security in the world or a sense of trust in themselves. They likely need more frequent reassurance to feel safe and loved. They may experience self-doubt and become risk averse.

People pleasing is one such way to navigate a world that feels socially unpredictable. It can arise in situations where parental disapproval is felt by a child, being an accommodating or compliant child is highly reinforced, and/or there is limited space for the child to take up emotionally in the family (e.g., a parent has anxiety, depression or a substance use disorder; or another sibling requires a lot of attention). People pleasing becomes a way to shore up a sense of love and belonging by eliciting approval and positive attention from others. Likewise, the strategy is utilized to avoid negative attention, conflict, and rejection from others.

Examples of people pleasing may include:

Accepting tasks from family members or friends you don’t actually want to do

Taking on tasks or projects at work to make you look like a “team player” when you don’t actually have the bandwidth, or it causes you to work overtime

Going out of your way to help someone and then feeling resentful about it later

Fear and avoidance of disappointing others

Feeling afraid to say ‘no’ to others requests

Why We Get Stuck

There are several myths which drive people pleasing:

“Worrying about someone is a sign of love”

“Feeling your pain means I care about you”

“If someone is hurting emotionally, then I am bad”

It’s easy to justify “niceness” as virtue, however, it’s important to recognize the difference between nice and kind. Nice is more compulsive or habitual. A compulsion is anything we do to rid ourselves of an unwanted thought or feeling. In this case, the uncomfortable thought could be “They are judging me negatively” or a feeling of disapproval. Because belonging is linked to our basic needs, people pleasing becomes more of a survival mechanism than a choice. As Dr. Kennedy says “our adaptations as children become our symptoms as adults.”

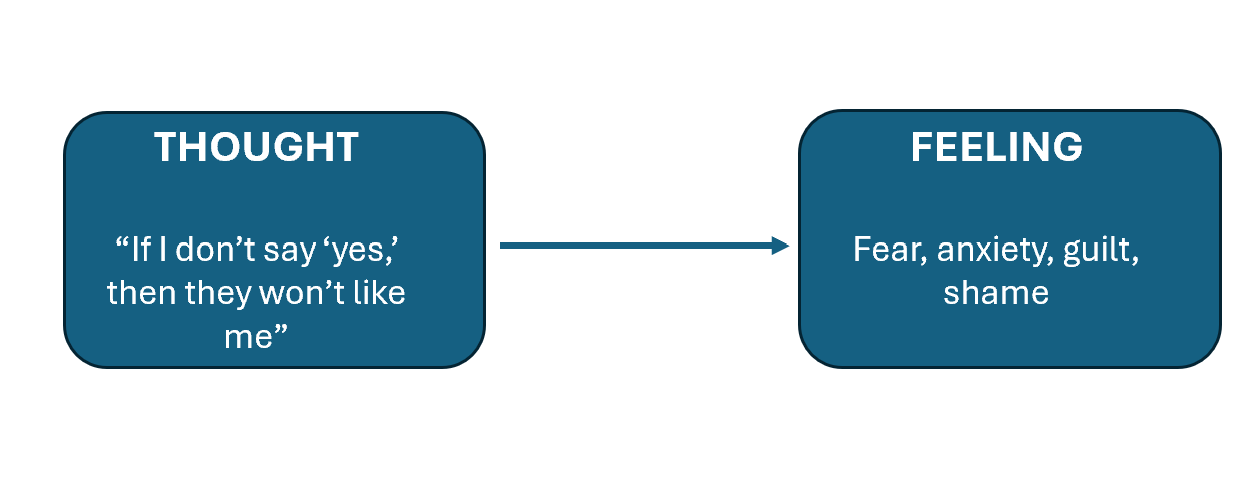

In Acceptance and Commitment therapy, we describe habitual behaviors as rigid and “hooked” meaning thoughts (e.g., “If I don’t accept their request, then they will stop loving me”) and feelings (e.g., fear, anxiety, guilt, shame) dominate our behavior. A thought like “they’ll be mad at me” can reel us in, demand our attention, and pull us into behavior that is ineffective for us in the long run.

In Acceptance and Commitment therapy (ACT), we describe habitual behaviors as rigid and “hooked” meaning thoughts and feelings dominate our behavior. A thought like “they’ll be mad at me” can reel us in, demand our attention, and pull us into behavior that is ineffective for us in the long run.

Photo by Sivani Bandaru on Unsplash

We say the behavior is under aversive control as in “I must do this thing to avoid this unwanted emotional experience (e.g., feelings of distress).” In Dr. Gazipura’s words, it can feel like other people’s feelings are “bank robbers holding guns at us.” This is the opposite of freedom.

The mind (specifically the part of us that is worried about belonging/rejection) uses fear to get us to pay attention and often self-attacking guilt to get us to do the behavior. Within this part of us that is attempting to shore up connection, there are infinite threats. As Dr. Aziz Gazipura says “If you’re worried about relationships (in this way), then you’re guarding the border 100% of the time. Ironically, we’d rather feel that awful guilt feeling than being with someone else having feelings.”

Notice how “should” as in “I should always be accommodating if I want others to like me” is one step away from fear which is a different motivation than deliberately choosing a value such as kindness, connection, love, integrity, or vitality. In his book, Less Nice, More You, Dr. Gazipura describes how the opposite of nice is not mean, it is authenticity. He shares research that demonstrates that chronic separation from truth (e.g., always being what we think others want us to be) can lead to G.I. problems and other health issues like migraines. We may rationalize and convince ourselves that we’re keeping the peace, especially if one of our roles in life is or was being a harmonizer, but it’s not internal peace. As he puts it, “we’re taking the hit internally.”

As with every behavior we do, there is a function (in this case, securing love) and a cost. People pleasing can overlap with social anxiety because in both cases it goes like this: we have an interaction and then the mind scans the interaction to make sure no one’s upset with us. Rinse and repeat. This is like “constantly running an app in the background” says Dr. Gazipura.

Eric Zimmer quoting the author Mary O’Malley says, “the mind is like a problem factory: not only is it replacing every problem that comes off the assembly line with a new one but it’s also constantly trying to adjust the current, past, or future moment in some way.” For example, assessing “how could I be more comfortable right now?” This sort of assessment was useful in primitive times to ensure survival (e.g., “Where will I find more blueberries? And what do I need to do to discover a new patch?”) but it’s not as useful now when overall our needs are more easily and reliably met, and rejection rarely means death the way it did centuries ago. So how do we learn to live in this mind?

The Path to Freedom

Bringing Awareness:

Once we decide people pleasing is no longer serving us, there is a path to liberating ourselves. First, we must acknowledge the behavior, identify the function and its costs, and then consider alternative beliefs and roles that serve us better such as building tolerance for others’ feelings. We forget our agency that, to some degree, “we hold the remote to the channels” (or the thinking patterns) in our mind. Often, the act of bringing awareness to something can change it.

See if you can catch yourself in the act of people pleasing or just after and ask:

“What type of thinking am I doing here?”

“What is driving this behavior?”

“Am I locked in a cycle of should and resentments?”

“Do I like the results (e.g., perhaps feeling validated but also feeling exhausted, depleted, irritable, socially avoidant, burned out)?”

“If not, what do I need to do to get out of this pattern?”

Next, notice how unworkable the pattern is: “because I can’t handle your bad feelings then I have to control your emotional state.” This basically suggests we believe the other person is not capable of managing their own emotions. Although some people will try to evoke responsibility in us for their emotions, when we say someone else can’t handle something it is often really a projection of our own feelings. When we say “I can’t break up with them because they won’t be able to handle it” is it possible that we are uncomfortable with their emotional distress and the distress that evokes in us? Operating as if we’re powerful enough to control another’s emotions positively (“I can make you happy”) or negatively (“I can make you feel better”) is a setup for failure in the long run. When we do the heavy lifting for another, they fail to learn the skills for themselves, and it perpetuates a cycle of dependence.

This doesn’t mean we are bad for trying to change others’ feelings. Recall that people pleasing is an adaptation or learned behavior we do in response to a set of difficult circumstances from earlier in our lives. We don’t need to criticize ourselves or banish this part of us; the best practice is to get curious.

Experiment with Reframing Thoughts and Beliefs that Empower (offered by Eric Zimmer and Dr. Gazipura):

“I can accept that loved ones are going to feel painful feelings, sometimes about me, sometimes related to something else in their life. I may be able to listen, sympathize, or empathize, AND I cannot control their feelings.”

“I can learn to accept and treat others as whole people who are resilient and able to manage their own emotions.”

“I’m here and I can be by your side, but your pain is yours to have and to hold and work through; it’s your teacher.”

This doesn’t mean we stop caring about others. Compassion is a superpower, but if used against us to get us to act in a certain way that is not in our best interests, we lose compassion for ourselves. So, do maintain the genuine desire for others wellbeing (e.g., “I genuinely care about you and don’t want you to hurt”) and learn to pull apart the value of compassion from the compulsion to people please.

Changing Behavior:

First gather some data. Bring to mind a relationship you find yourself people pleasing in and write out the top 10 beliefs you hold about how you should behave in the relationship. Identify extremes like “I must always be available to them.” Inquire if they put you in that role explicitly or if you took on that role without them asking you to.

Rewrite the script: Dr. Gazipura suggests writing a Bill of Rights where you consider how you want to behave in relationships such as “I have a right to say ‘no;” or “I have a right to consult my bandwidth before committing to anything.”

Distress tolerance is a tool for regulating our emotions and cultivating more peace in our lives. Rather than approaching others feelings as “how do I get that bad feeling out of the room?” we can learn to tolerate discomfort.

Photo by Isaac Burke on Unsplash

My favorite analogy goes like this:

“What happens when you get into a cold pool?”

Most people will answer, “It’s wildly uncomfortable and I have the urge to get out!”

So I ask them, “And then what happens?”

And most people say “You get used to it.”

The same is true of stepping outside our comfort zone and learning to tolerate distress (ours and others). The ultimate goal is to relax the nervous system to allow your body to adjust to the cold or discomfort. However, we may never feel totally relaxed or calm in cold water. Occasionally acting in accordance with our values feels totally serene but more often than not going after what really matters to us in life is accompanied by some discomfort.

So when feeling internal discomfort about another’s feelings, ask yourself: “Can I relax into it? What tools do I need in order to tolerate this?”

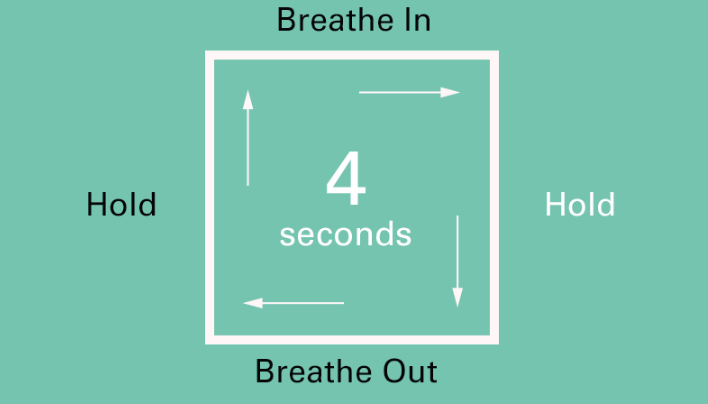

Learn Box Breathing

Box breathing is simple breathing exercise that can help us cope with intense emotions. Follow this graphic to inhale for 4 seconds, hold the breath for 4 seconds, exhale for 4 seconds, and hold for 4 seconds. Repeat as many times as is useful although if you become light headed, return to your natural breathing pattern.

TIPS

TIP Skills are another set of tools that can assist us in regulating our emotions. For example, the “T” in TIP stands for temperature. We can hold ice cubes, frozen bananas, or a package of frozen peas in our hands to reduce sympathetic nervous system activation aka “fight-flight-freeze” when we are feeling uncomfortable emotions.

By working at it, we can learn to tolerate distress, ours and others, in the service of our values. We can learn to move more freely through the world, being more deliberate about the actions we choose, how we interact with others, acting like the kind of person we want to be. “Unhooked” in ACT means thoughts and feelings no longer dominate or jerk us around or take up all our attention. They lose their impact and influence over us, so it’s easier to choose how we behave.

Imaginal Work

Use distress tolerance tools when you start to have the thought “They’re mad at me,” running forecasts or replays of the interaction, or fixating on “damage control” in the relationship. With enough practice, you’ll be able to use them in the moment.

4. Discernment

It’s still okay to act with kindness! Just know you are doing it; act with intention. One way to evaluate if we’re acting nice or kind is how we feel after. Dr. Gazipura says:

Kindness leaves the flow of joy

Niceness leaves the residue of resentment (It’s a ‘have to’)

References & Resources:

The One You Feed Podcast hosted by Eric Zimmer, interview with Dr. Aziz Gazipura

Podcast: https://www.goodinside.com/podcast/

Podcast interviews:

Books:

Attached: The New Science of Adult Attachment and How it Can Help You Find and Keep Love by Amir Levine and Rachel Heller, 2012

Videos and Books on ACT:

How to get unhooked https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vKE9e8pgrg8

The Happiness Trap by Russ Harris https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/3250347; https://thehappinesstrap.com/free-resources/